【Automate the Boring Stuff with Python Practical Programming for Total Beginners】

Chapter 1. Python Basics

Covers expressions, the most basic type of Python instruction, and how to use the Python interactive shell software to experiment with code.

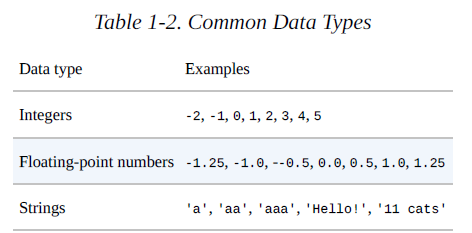

The Integer, Floating-Point, and String Data Types

String Concatenation and Replication

Storing Values in Variables

Assignment Statements

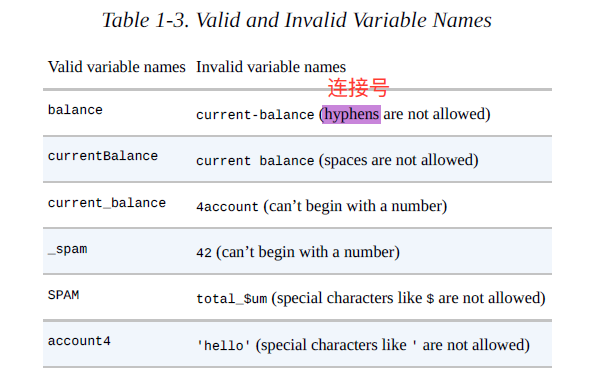

Variable Names

\1. It can be only one word.

\2. It can use only letters, numbers, and the underscore (_) character.

\3. It can’t begin with a number.

\4. It is a Python convention to start your variables with a lowercase letter.

Dissecting Your Program

Comments

The print() Function

When writing a function name, the opening and closing parentheses at the end identify it

as the name of a function. This is why in this book you’ll see print() rather than print.

The input() Function

The len() Function

The str(), int(), and float() Functions

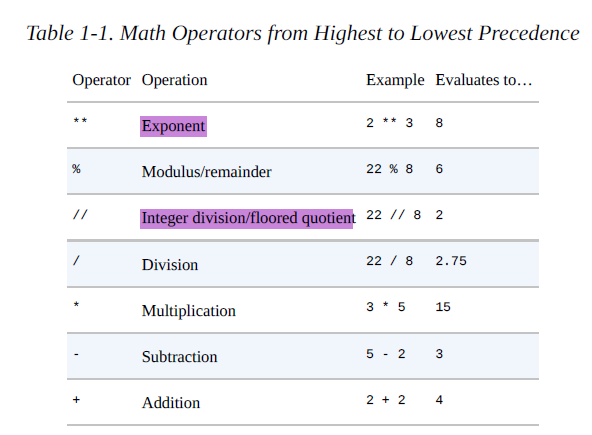

It is good to remember the different types of operators (+, -, *, /, //, %, and ** for math

operations, and + and * for string operations) and the three data types (integers, floatingpoint

numbers, and strings) introduced in this chapter.

Chapter 2. Flow Control

Explains how to make programs decide which instructions to execute so your code can intelligently respond to different conditions.

Boolean Values

the Boolean values True and False lack the quotes you place around strings, and they always start with a capital T or F

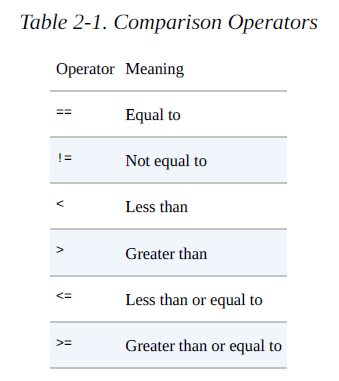

Comparison Operators

Comparison operators compare two values and evaluate down to a single Boolean value.

(THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE == AND = OPERATORS)

Boolean Operators

three Boolean operators (and, or, and not)

Binary Boolean Operators

The not Operator

Mixing Boolean and Comparison Operators

>>> 2 + 2 == 4 and not 2 + 2 == 5 and 2 * 2 == 2 + 2

True

Elements of Flow Control

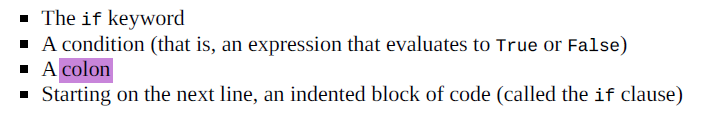

Flow control statements start with conditions, and all are followed by

a block of code called the clause.

Conditions

Blocks of Code

\1. Blocks begin when the indentation increases.

\2. Blocks can contain other blocks.

\3. Blocks end when the indentation decreases to zero or to a containing block’s indentation.

Program Execution(f5)

Flow Control Statements

if Statements

else Statements

An if clause can optionally be followed by an else statement.

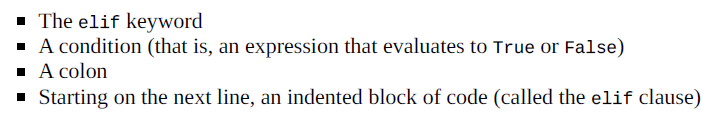

elif Statements

while Loop Statements

**break Statements

There is a shortcut to getting the program execution to break out of a while loop’s clause early. If the execution reaches a break statement, it immediately exits the while loop’s clause. In code, a break statement simply contains the break keyword.

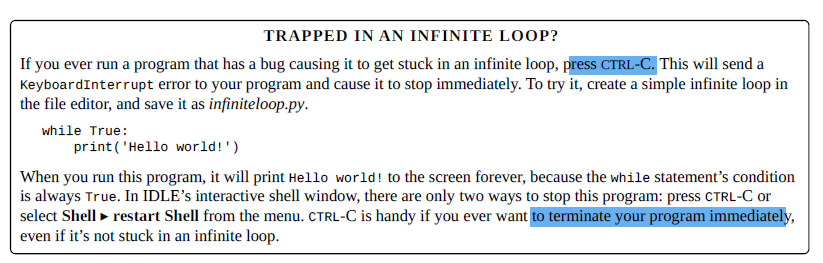

(An infinite loop that never exits is a common programming bug.)

**continue Statements

continue statements are used inside loops. When the program execution reaches a continue statement, the program execution immediately jumps back to the start of the loop and reevaluates the loop’s condition. (This is also what happens when the execution reaches the end of the loop.)

(Ctrl+C to terminate program immediately.)

You can use continue and break statements only inside while and for loops.

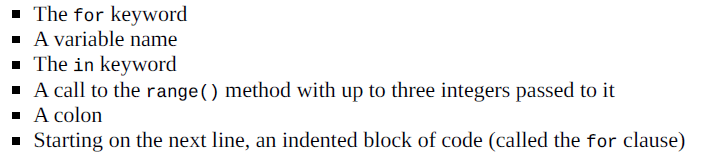

for Loops and the range() Function

The Starting, Stopping, and Stepping Arguments to range()

The range() function is flexible in the sequence of numbers it produces for for loops. For example (I never apologize for my puns), you can even use a negative number for the step argument to make the for loop count down instead of up.

for i in range(5, -1, -1):

print(i)

Running a for loop to print i with range(5, -1, -1) should print from five down to

zero.

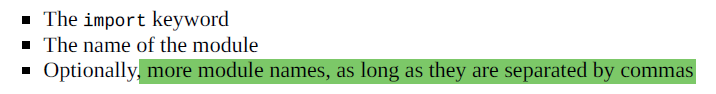

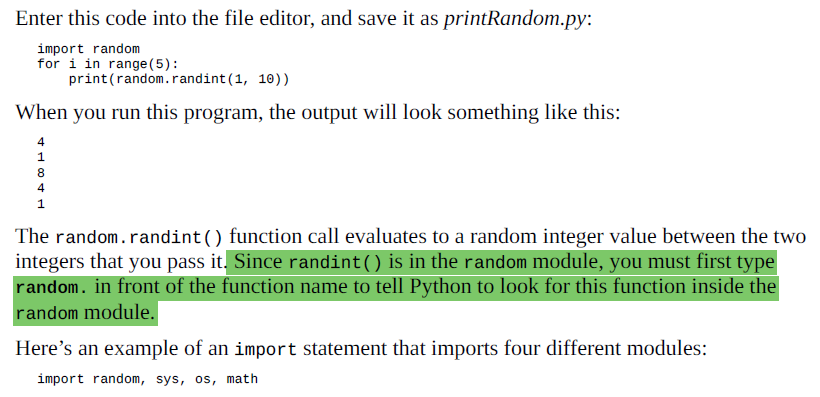

Importing Modules

from import Statements

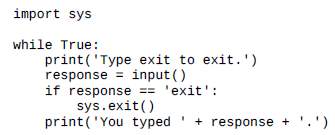

Ending a Program Early with sys.exit()

The last flow control concept to cover is how to terminate the program. This always happens if the program execution reaches the bottom of the instructions. However, you can cause the program to terminate, or exit, by calling the sys.exit() function. Since this function is in the sys module, you have to import sys before your program can use it. Open a new file editor window and enter the following code, saving it as exitExample.py:

**

Chapter 3. Functions

Instructs you on how to define your own functions so that you can organize your code into more manageable chunks.

A function is like a mini-program within a program.

defines a function named ; the body of the function; function calls.

A major purpose of functions is to group code that gets executed multiple times.

def Statements with Parameters

➊. A parameter is a variable that an argument is stored in when a function is called. ➋. One special thing to note about parameters is that the value stored in a parameter is forgotten when the function returns. This is similar to how a program’s variables are forgotten when the program terminates.

Return Values and return Statements

Remember, expressions are composed of values and operators. A function call can be used in an expression because it evaluates to its return value.

The None Value

In Python there is a value called None, which represents the absence of a value.

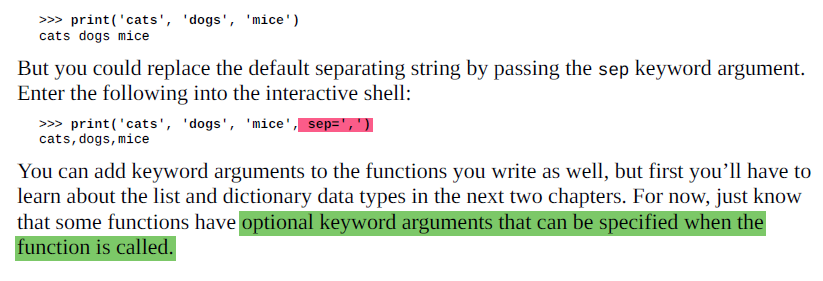

Keyword Arguments and print()

**end=’‘

**sept=’,’

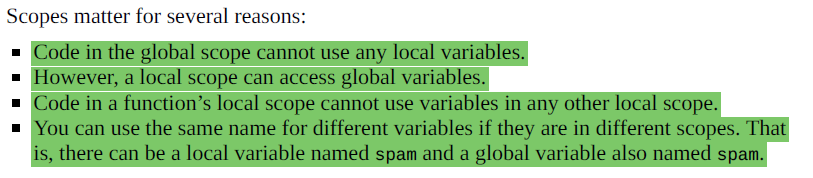

Local and Global Scope

Parameters and variables that are assigned in a called function are said to exist in that function’s local scope. Variables that are assigned outside all functions are said to exist in the global scope. A variable that exists in a local scope is called a local variable, while a variable that exists in the global scope is called a global variable. A variable must be one or the other; it cannot be both local and global.

A local scope is created whenever a function is called.

The reason Python has different scopes instead of just making everything a global variable is so that when variables are modified by the code in a particular call to a function, the function interacts with the rest of the program only through its parameters and the return value.

While using global variables in small programs is fine, it is a bad habit to rely on global variables as your programs get larger and larger.

Local Variables Cannot Be Used in the Global Scope

Local Scopes Cannot Use Variables in Other Local Scopes

A new local scope is created whenever a function is called, including when a function is called from another function. Consider this program.

Multiple local scopes can exist at the same time.

The upshot is that local variables in one function are completely separate from the local variables in another function.

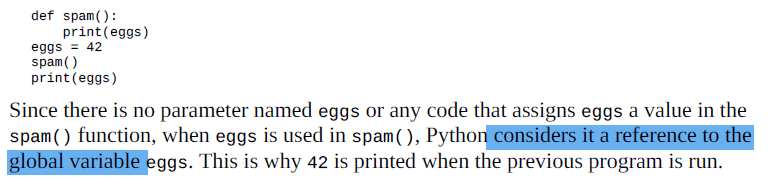

Global Variables Can Be Read from a Local Scope

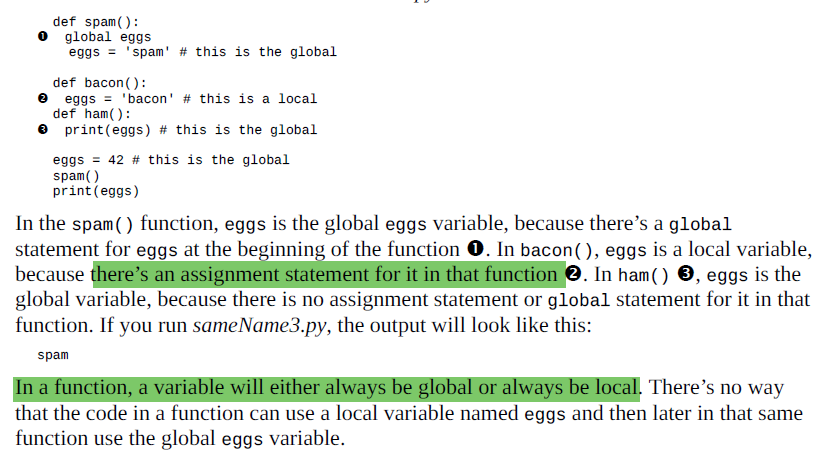

Local and Global Variables with the Same Name

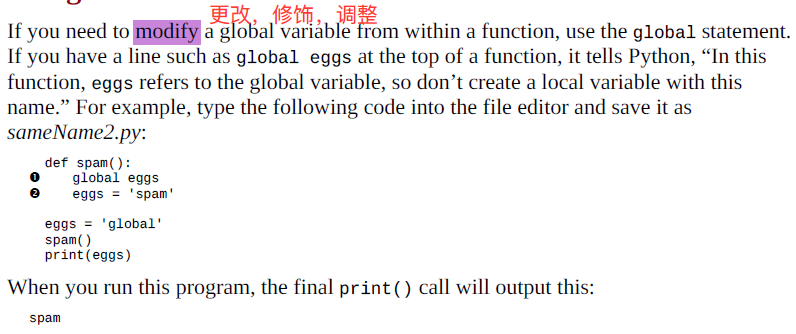

The global Statement

There are four rules to tell whether a variable is in a local scope or global scope:

\1. If a variable is being used in the global scope (that is, outside of all functions), then it is always a global variable.

\2. If there is a global statement for that variable in a function, it is a global variable.

\3. Otherwise, if the variable is used in an assignment statement in the function, it is a local variable.

\4. But if the variable is not used in an assignment statement, it is a global variable.

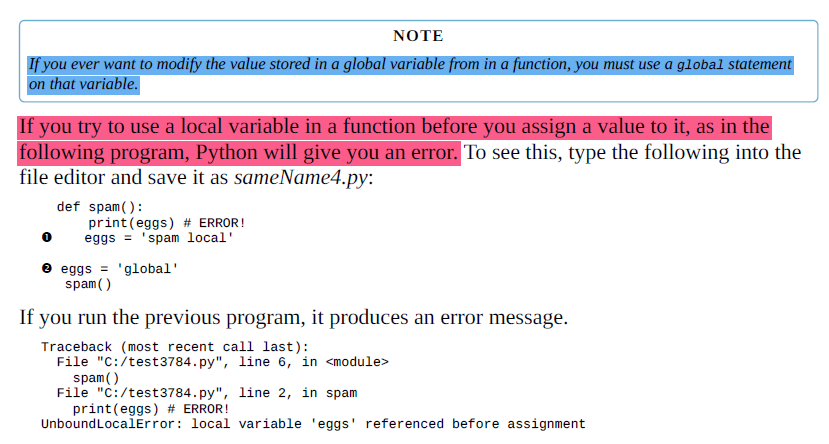

This error happens because Python sees that there is an assignment statement for eggs in the spam() function ➊ and therefore considers eggs to be local. But because print(eggs) is executed before eggs is assigned anything, the local variable eggs doesn’t exist. Python will not fall back to using the global eggs variable ➋.

FUNCTIONS AS “BLACK BOXES”

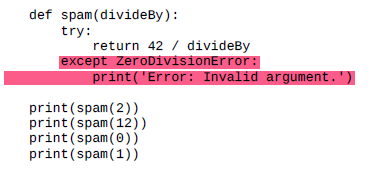

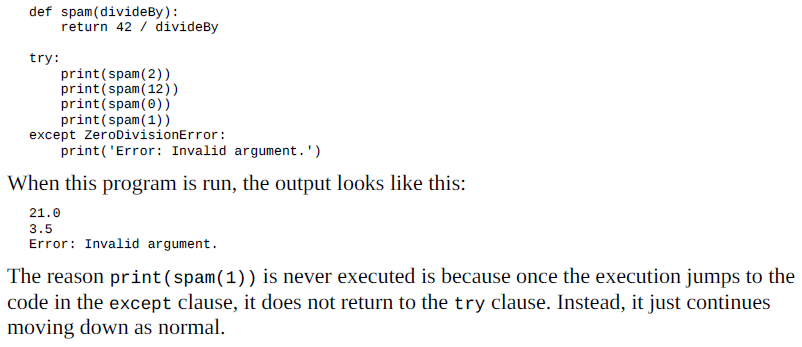

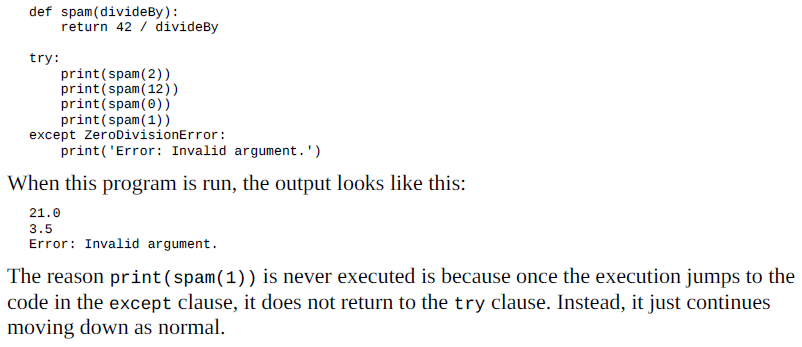

Exception Handling

Errors can be handled with try and except statements.

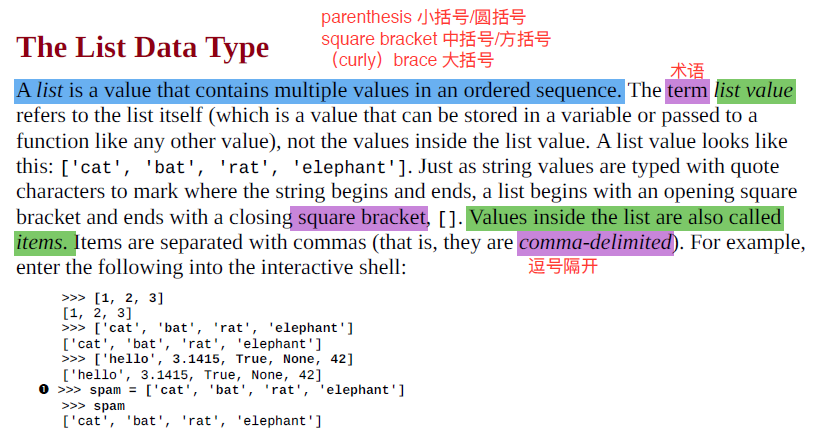

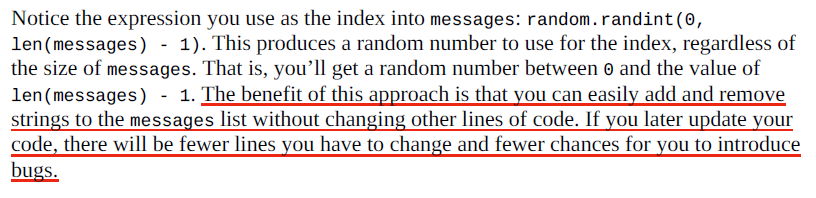

### Chapter 4. Lists

Introduces the list data type and explains how to organize data.

)

)

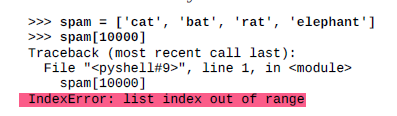

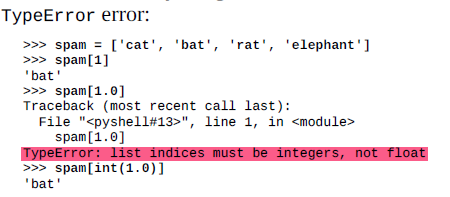

Getting Individual Values in a List with Indexes

The integer inside the square brackets that follows the list is called an

index.

Negative Indexes

The integer value -1 refers to the last index in a list.

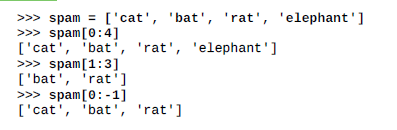

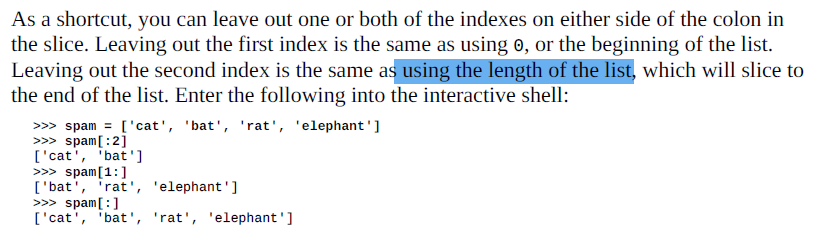

Getting Sublists with Slices

Just as an index can get a single value from a list, a slice can get several values from a list, in the form of a new list.

Getting a List’s Length with len()

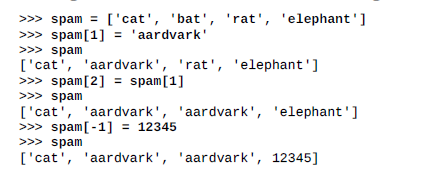

Changing Values in a List with Indexes

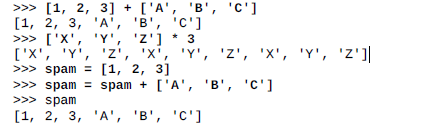

List Concatenation and List Replication

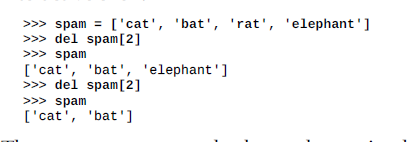

Removing Values from Lists with del Statements

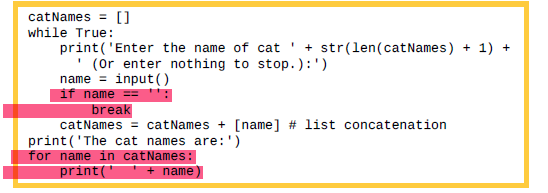

Working with Lists

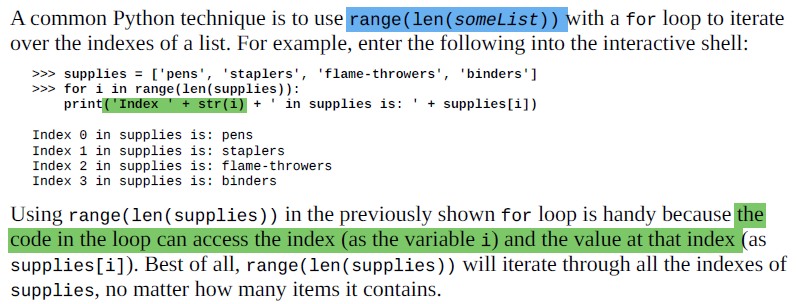

*Using for Loops with Lists

The in and not in Operators

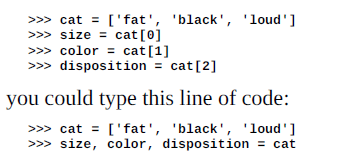

The Multiple Assignment Trick

The number of variables and the length of the list must be exactly equal, or Python will give you a ValueError.

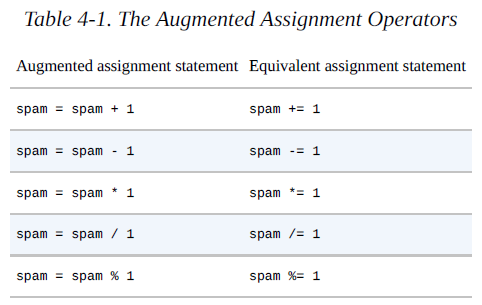

Augmented Assignment Operators

The += operator can also do string and list concatenation:

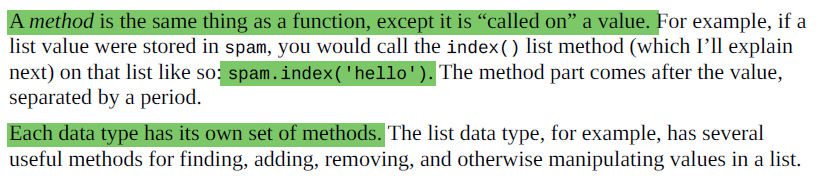

Methods

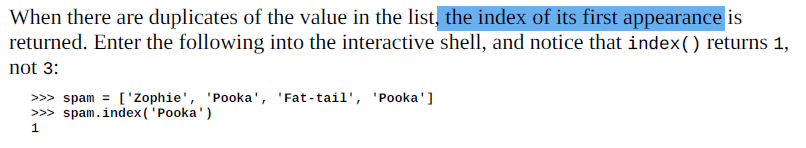

Finding a Value in a List with the index() Method

Adding Values to Lists with the append() and insert() Methods

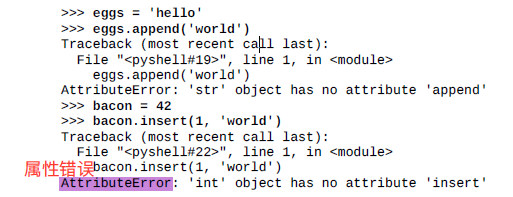

Methods belong to a single data type. The append() and insert() methods are list methods and can be called only on list values, not on other values such as strings or integers.

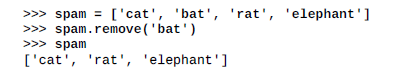

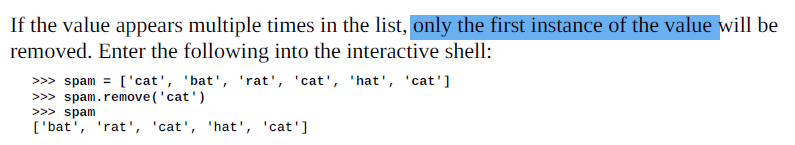

*Removing Values from Lists with remove()

»>spam.remove(‘bat’) equals to del spam[1]

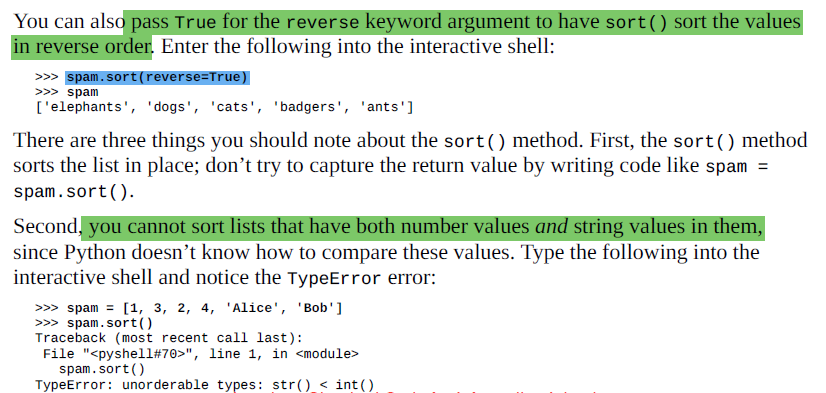

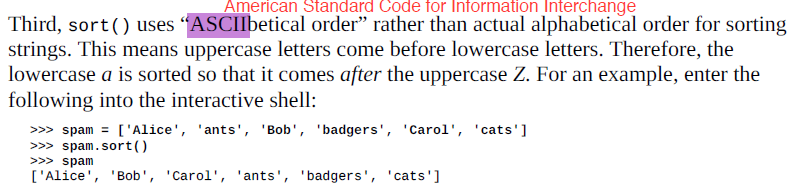

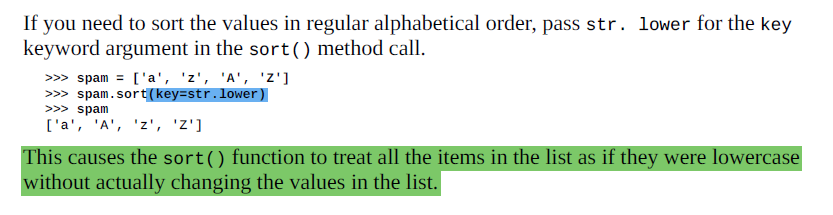

Sorting the Values in a List with the sort() Method

List-like Types: Strings and Tuples

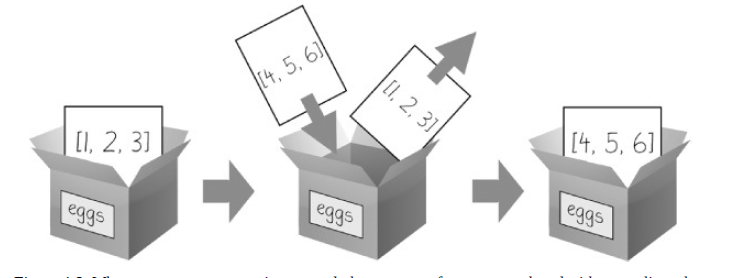

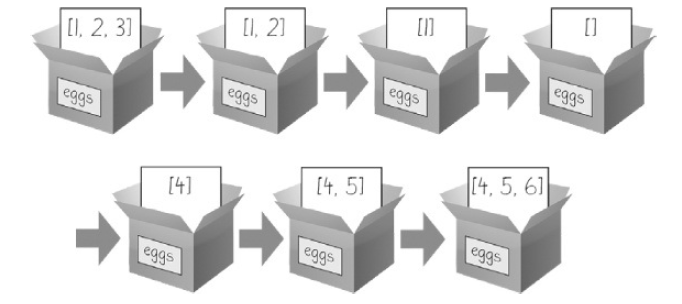

Mutable and Immutable Data Types

(The difference between overwriting and modifying.)

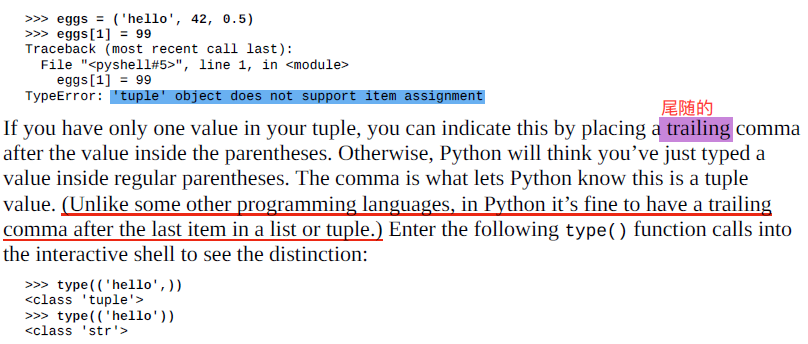

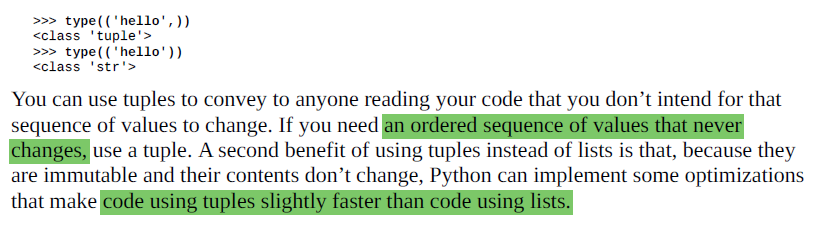

The Tuple Data Type

tuples are typed with parentheses, ( and ), instead of square brackets, [ and ].

that tuples, like strings, are

immutable.

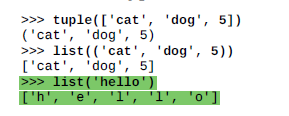

Converting Types with the list() and tuple() Functions

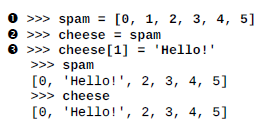

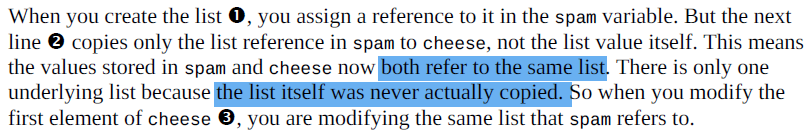

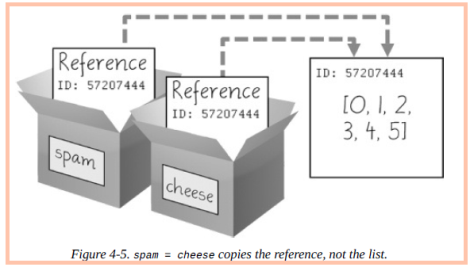

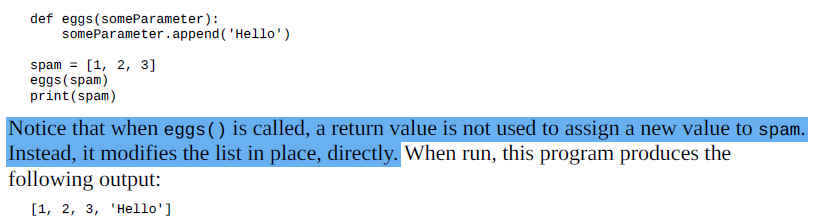

*References

Variables will contain references to list values rather than list values themselves. But for strings and integer values, variables simply contain the string or integer value. Python uses references whenever variables must store values of mutable data types, such as lists or dictionaries. For values of immutable data types such as strings, integers, or tuples, Python

variables will store the value itself.

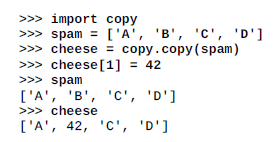

*The copy Module’s copy() and deepcopy() Functions

If the list you need to copy contains lists, then use the copy.deepcopy() function instead of copy.copy(). The deepcopy() function will copy these inner lists as well.

Chapter 5. Dictionaries and Structuring Data

Introduces the dictionary data type and shows you more powerful ways to organize data.

Dictionaries vs. Lists

Unlike lists, items in dictionaries are unordered.

Because dictionaries are not ordered, they can’t be sliced like lists.

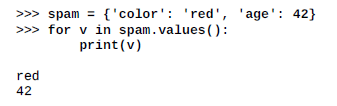

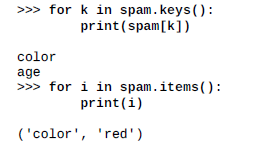

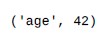

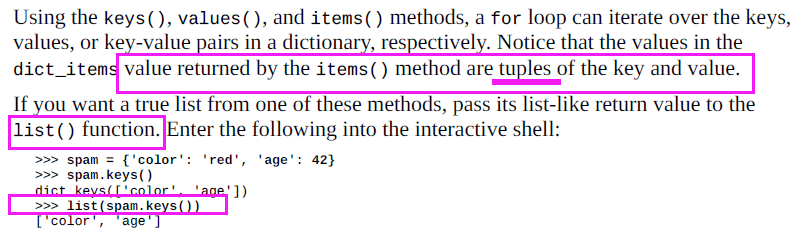

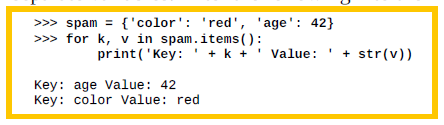

The keys(), values(), and items() Methods

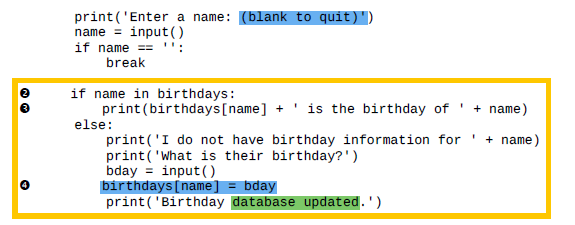

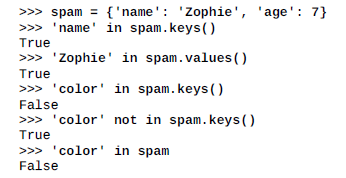

Checking Whether a Key or Value Exists in a Dictionary

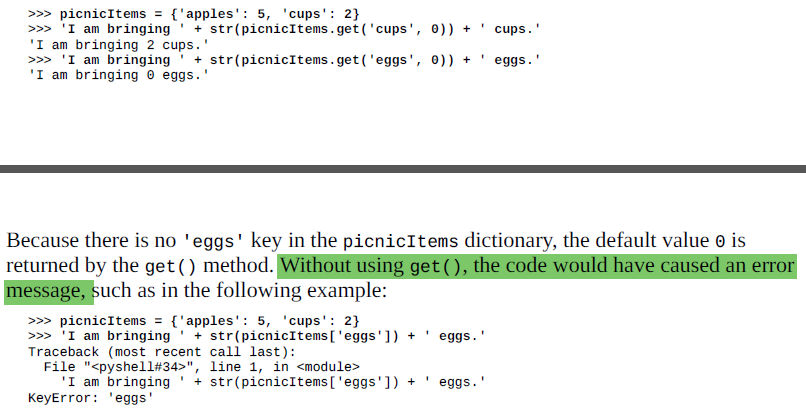

The get() Method

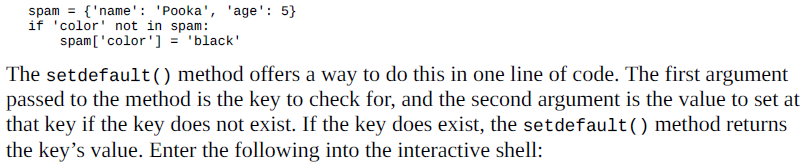

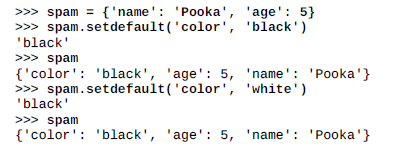

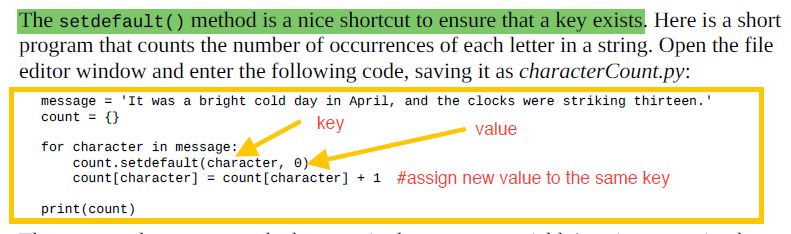

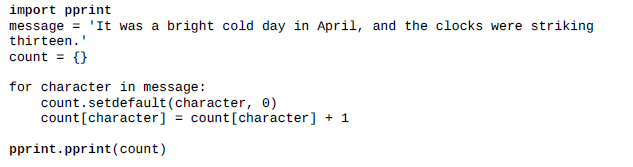

**The setdefault() Method

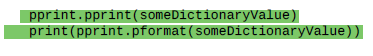

Pretty Printing

Using Data Structures to Model Real-World Things

Nested Dictionaries and Lists

Chapter 6. Manipulating Strings

Covers working with text data (called strings in Python).

Working with Strings

Double Quotes

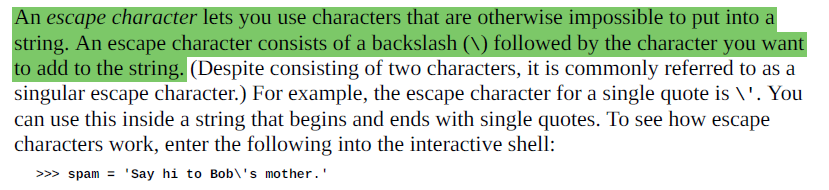

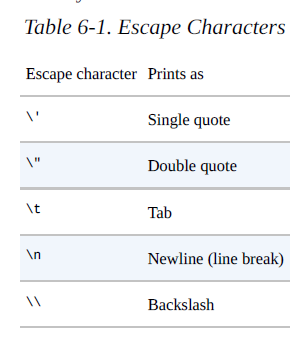

Escape Characters

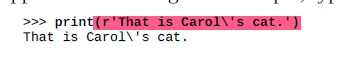

Raw Strings

Multiline Strings with Triple Quotes

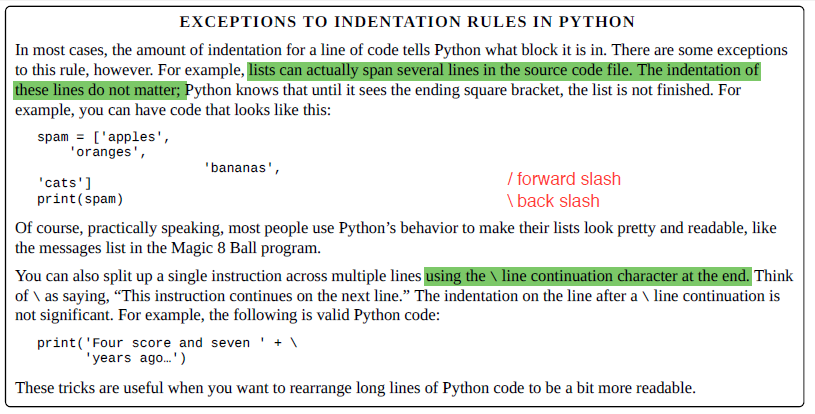

string. Python’s indentation rules for blocks do not apply to lines inside a multiline string.

Multiline Comments

Indexing and Slicing Strings

The in and not in Operators with Strings

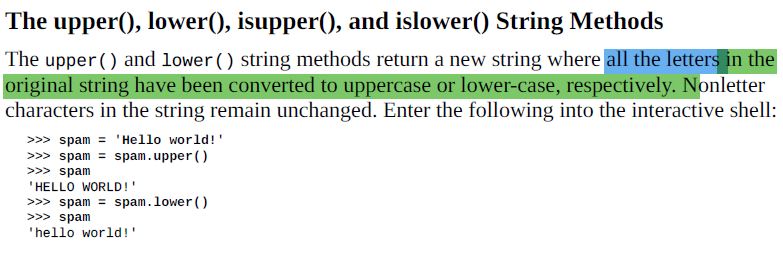

Useful String Methods

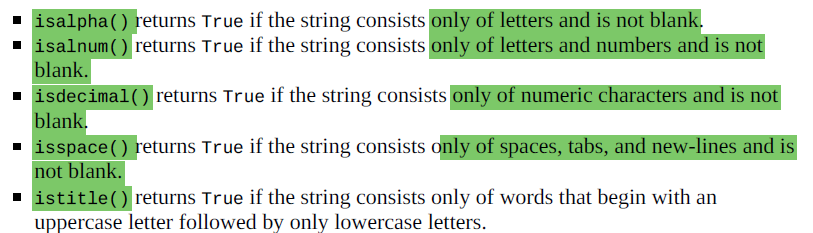

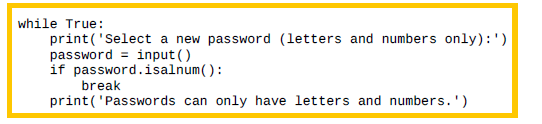

The isX String Methods

The startswith() and endswith() String Methods

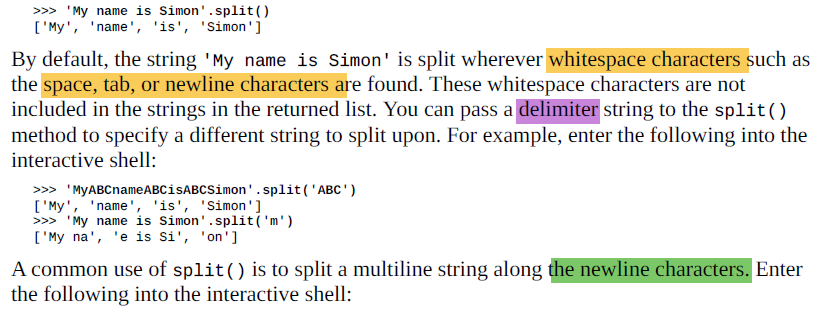

The join() and split() String Methods

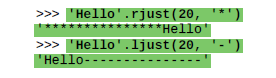

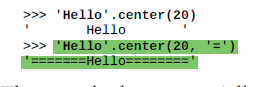

Justifying Text with rjust(), ljust(), and center()

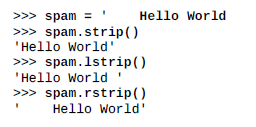

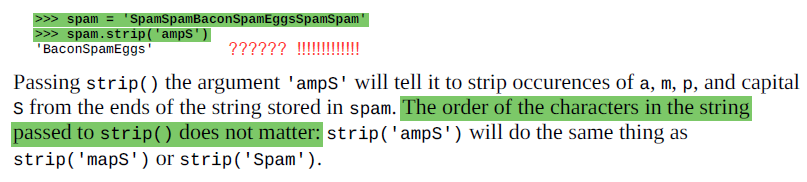

Removing Whitespace with strip(), rstrip(), and lstrip()

Copying and Pasting Strings with the pyperclip Module

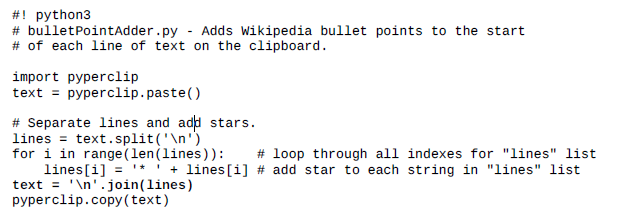

Project: Adding Bullets to Wiki Markup

Step 1: Copy and Paste from the Clipboard

Step 2: Separate the Lines of Text and Add the Star

Step 3: Join the Modified Lines

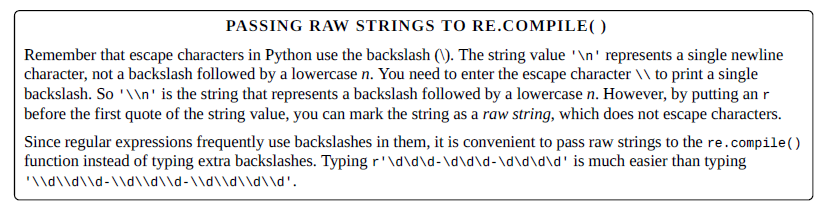

### Chapter 7. Pattern Matching with Regular Expressions

Covers how Python can manipulate strings and search for text patterns with regular expressions.

Finding Patterns of Text Without Regular Expressions

Finding Patterns of Text with Regular Expressions

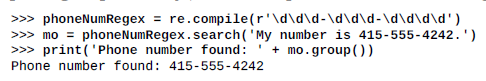

Creating Regex Objects

>>> import re

>>> phoneNumRegex = re.compile(r’\d\d\d-\d\d\d-\d\d\d\d’)

Matching Regex Objects

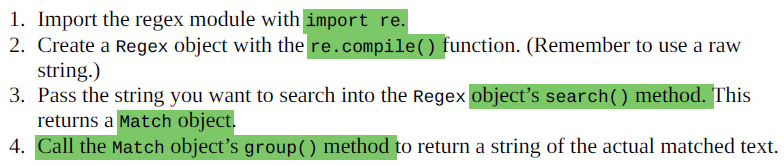

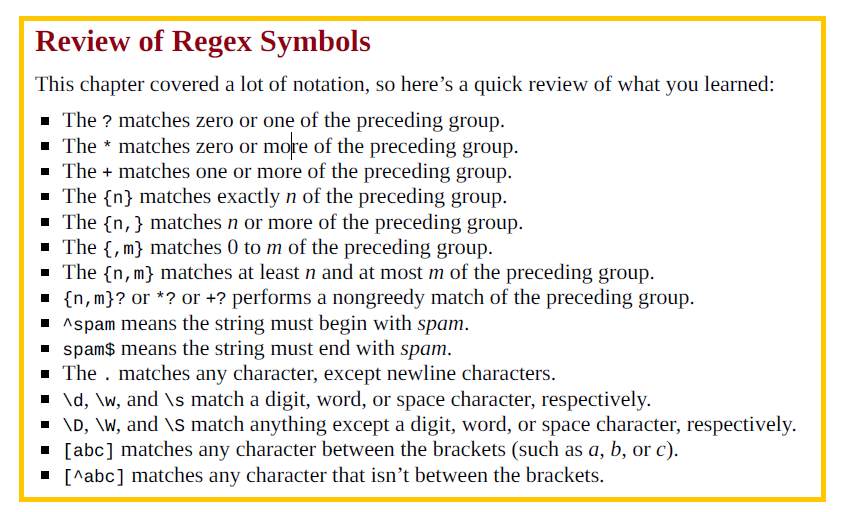

**Review of Regular Expression Matching

More Pattern Matching with Regular Expressions

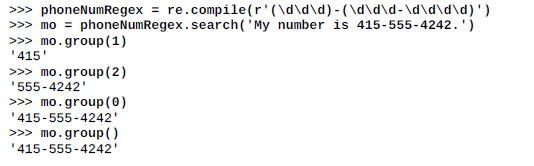

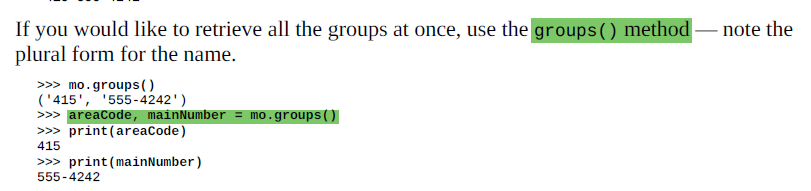

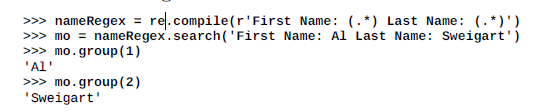

Grouping with Parentheses

Adding parentheses will create groups in the regex: (\d\d\d)-(\d\d\d-\d\d\d\d).

Passing 0 or nothing to the group() method will return the entire matched text.

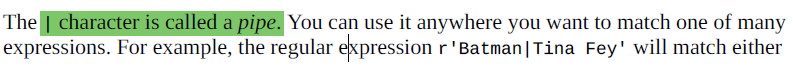

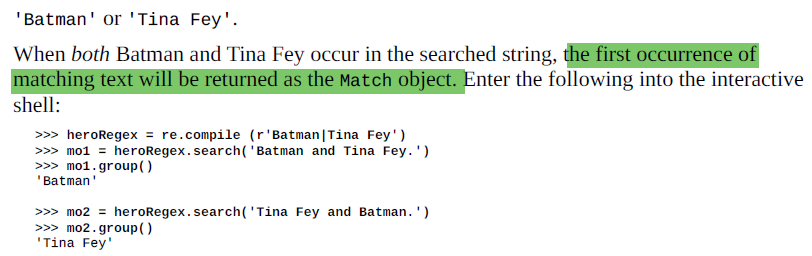

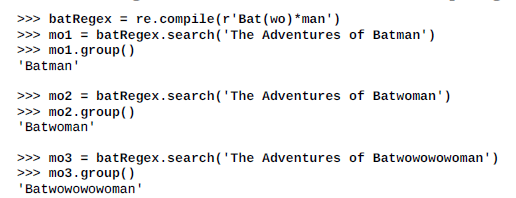

*Matching Multiple Groups with the Pipe

Optional Matching with the Question Mark

You can think of the ? as saying, “Match zero or one of the group preceding this question mark.”

If you need to match an actual question mark character, escape it with \?.

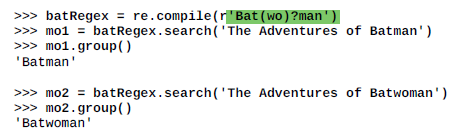

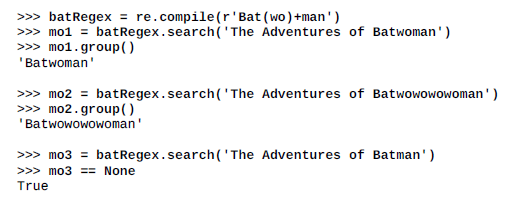

Matching Zero or More with the Star

The * (called the star or asterisk) means “match zero or more” — the group that precedes the star can occur any number of times in the text.

If you need to match an actual star character, prefix the star in the regular expression with a backslash, \*.

Matching One or More with the Plus

If you need to match an actual plus sign character, prefix the plus sign with a backslash to escape it: \+.

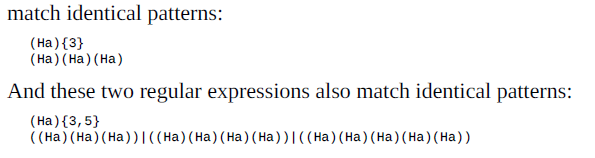

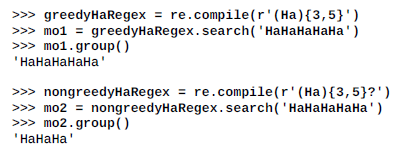

*Matching Specific Repetitions with Curly Brackets

For example, the regex (Ha){3} will match the string ‘HaHaHa’, but it will not match ‘HaHa’, since the latter has only two repeats of the (Ha) group.

For example, (Ha){3,} will match three or more instances of the (Ha) group, while (Ha){,5} will match zero to five instances.

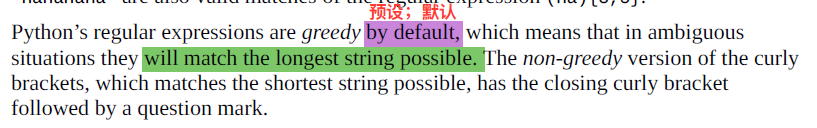

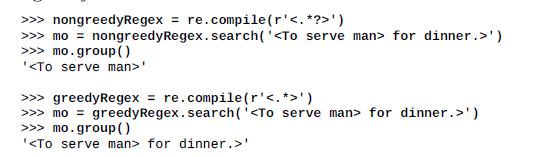

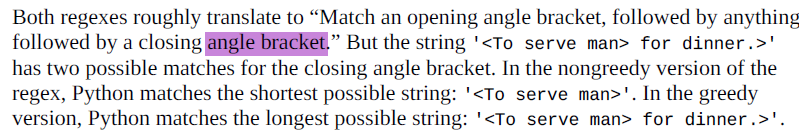

Greedy and Nongreedy Matching

Note that the question mark can have two meanings in regular expressions: declaring a nongreedy match or flagging an optional group.

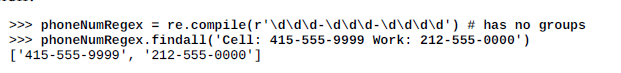

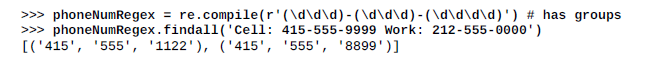

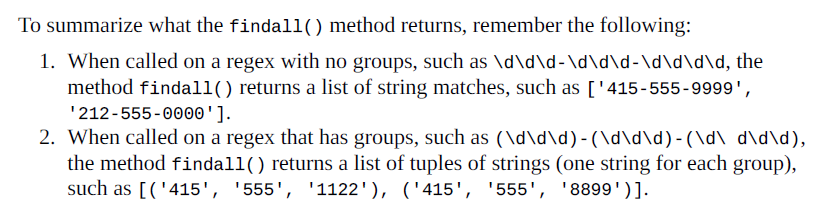

*The findall() Method

findall() will not return a Match object but a list of strings — as long

as there are no groups in the regular expression.

If there are groups in the regular expression, then findall() will return a list of tuples.

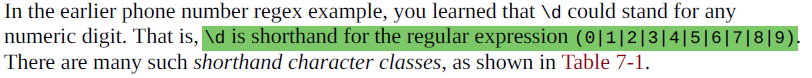

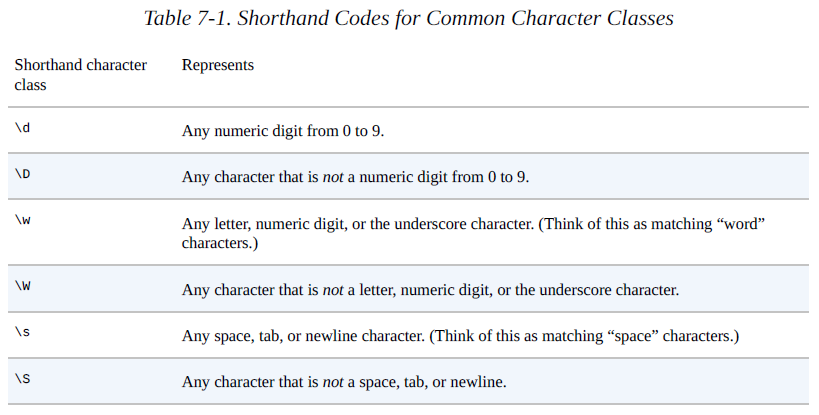

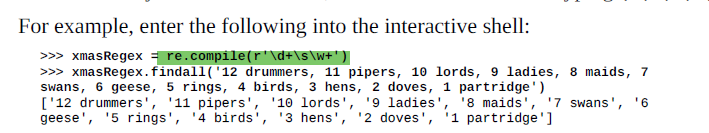

*Character Classes

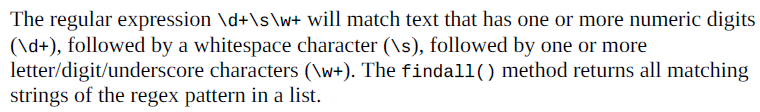

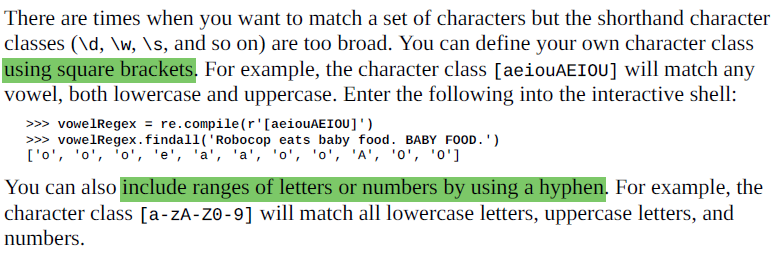

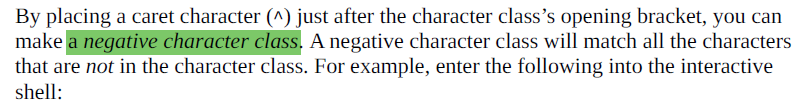

*Making Your Own Character Classes

Now, instead of matching every vowel, we’re matching every character that isn’t a vowel.

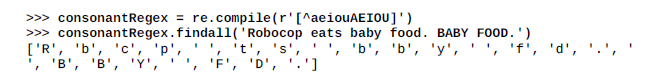

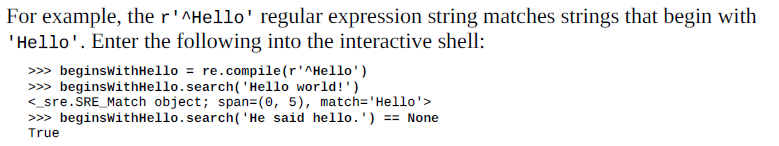

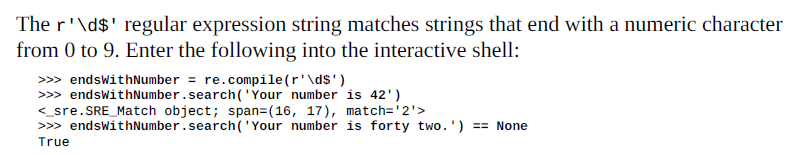

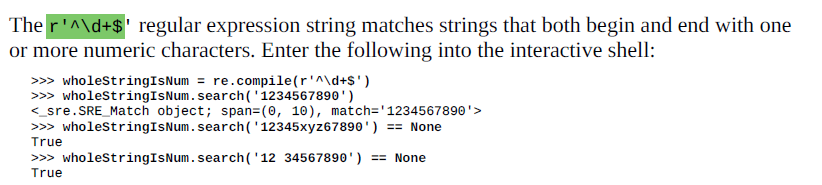

*The Caret and Dollar Sign Characters

**“Carrots cost dollars”

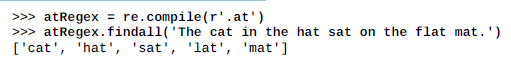

**The Wildcard Character

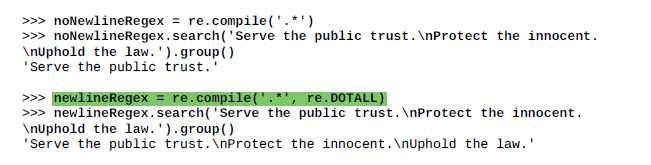

The . (or dot) character in a regular expression is called a wildcard and will match any character except for a newline.

Matching Everything with Dot-Star

Matching Newlines with the Dot Character

**Review of Regex Symbols

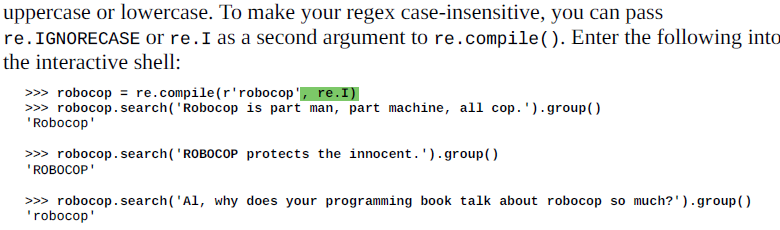

Case-Insensitive Matching

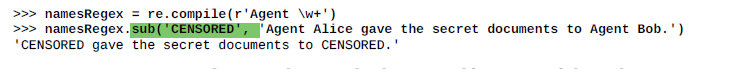

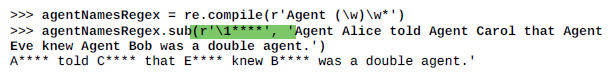

Substituting Strings with the sub() Method

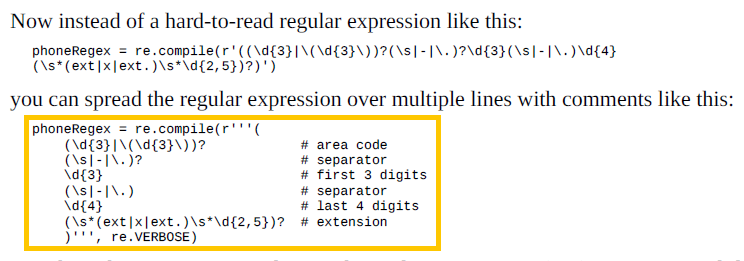

Managing Complex Regexes

This “verbose mode” can be enabled by passing the variable re.VERBOSE as the second argument to re.compile().

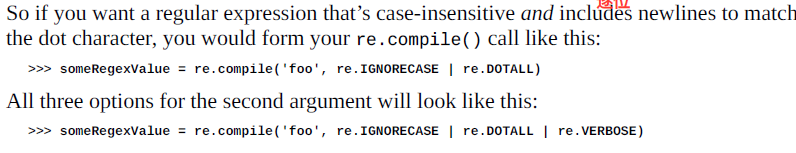

*Combining re.IGNORECASE, re.DOTALL, and re.VERBOSE

**

Chapter 8. Reading and Writing Files

Explains how your programs can read the contents of text files and save information to files on your hard drive. How to use Python to create, read, and save files on the hard drive

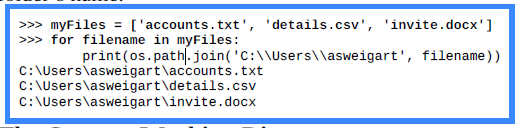

Files and File Paths

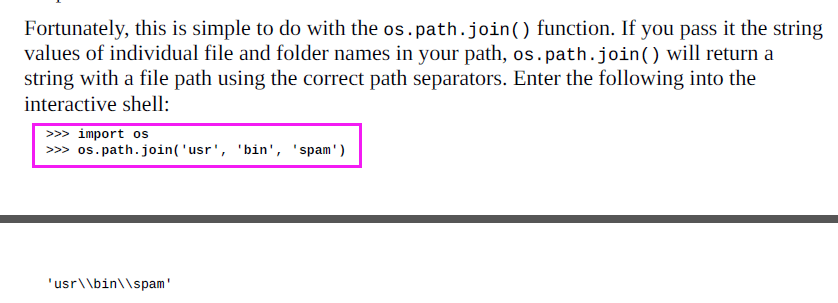

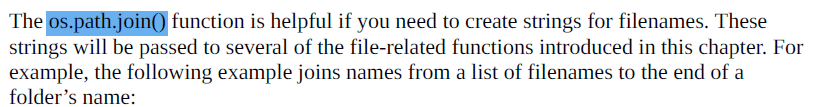

Backslash on Windows and Forward Slash on OS X and Linux

On Windows, paths are written using backslashes (*)** as the separator between folder names. OS X and Linux, however, use the forward slash (/*) as their path separator. If you want your programs to work on all operating systems, you will have to write your Python scripts to handle both cases.

‘usr\bin\spam’

‘usr\bin\spam’

>>>import os

print(os.path.join(‘F:\’,’mindi abair’,’works’,’ace’))

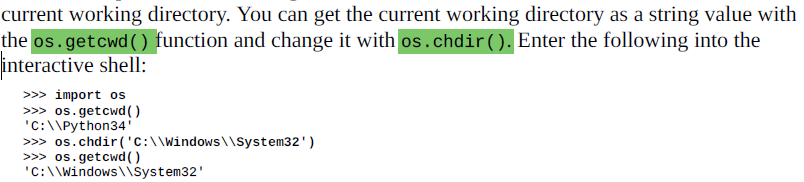

The Current Working Directory

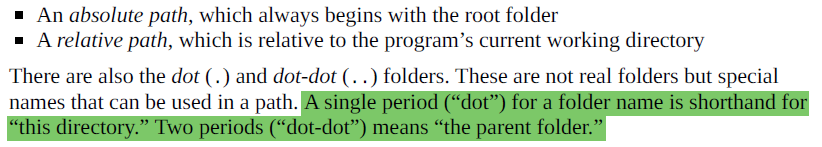

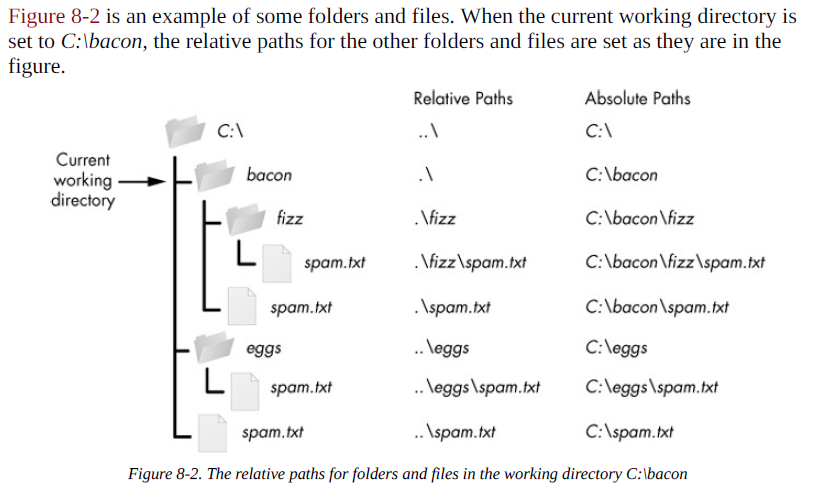

Absolute vs. Relative Paths

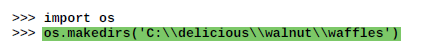

*Creating New Folders with os.makedirs()

That is, os.makedirs() will create any necessary intermediate folders in order to ensure that the full path exists.

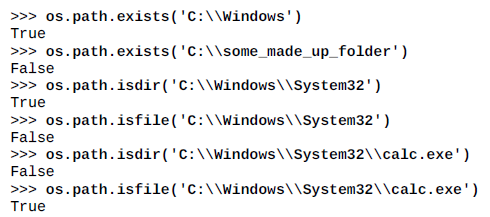

*The os.path Module

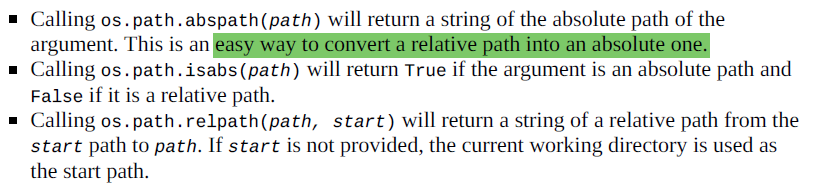

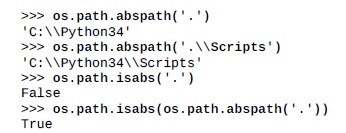

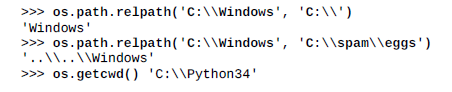

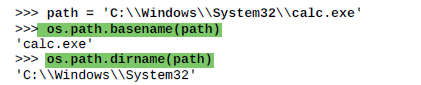

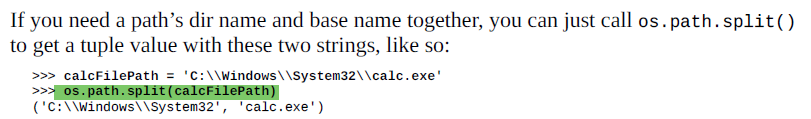

Handling Absolute and Relative Paths

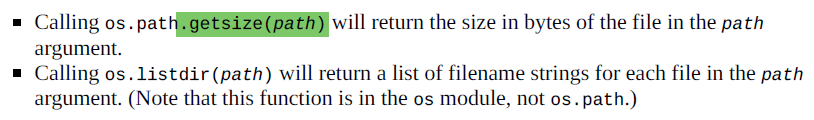

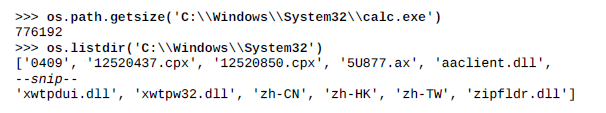

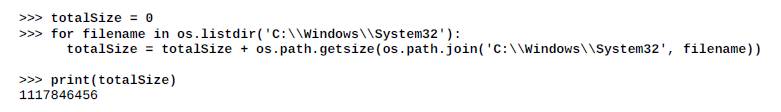

Finding File Sizes and Folder Contents

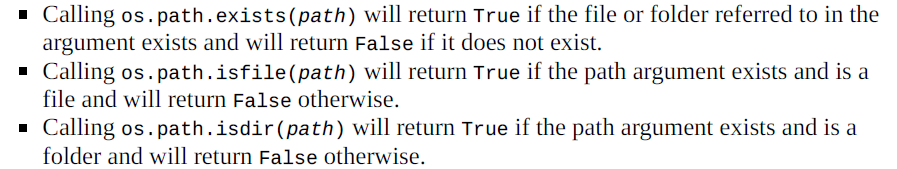

Checking Path Validity

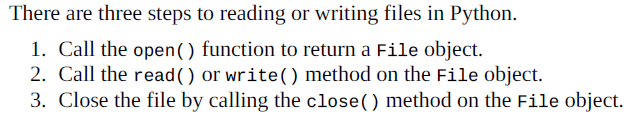

**The File Reading/Writing Process**

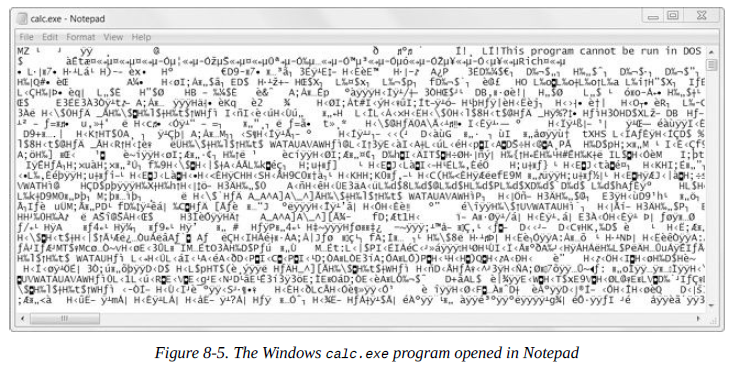

Plaintext files*** contain only basic text characters and do not include font, size, or color information. Text files with the **.txt* extension or Python

script files with the *.py* extension are examples of plaintext files.

*Binary files* are all other file types, such as word processing documents, PDFs, images, spreadsheets, and executable programs.

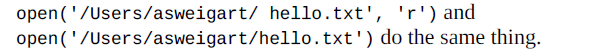

Opening Files with the open() Function

The call to open() returns a File object. A File object represents a file on your computer; it is simply another type of value in Python, much like the lists and dictionaries you’re already familiar with.

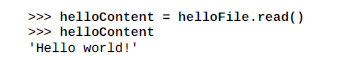

***Reading the Contents of Files**

the contents of a file as a single large string value

readlines()*** **method* to get a list of string values from the file, one string for each line of text.

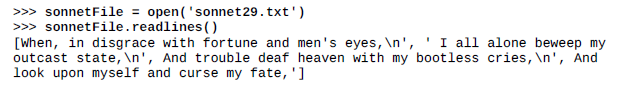

Writing to Files

You can’t write to a file you’ve opened in read mode, though. Instead, you need to open it in “write plaintext” mode or “append plaintext” mode, or write mode and append mode for short.

import os

defeat=open(‘F:\mindi abair\works\deff.txt’,’a’) #open or create a new txt

defeat.write(‘Life is short.\nYou took it for granted, then it's gone.\n’)

defeat.close()

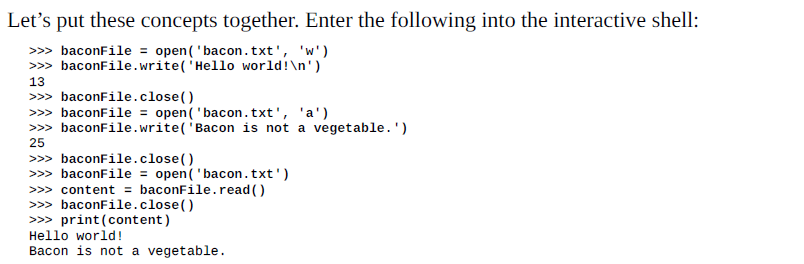

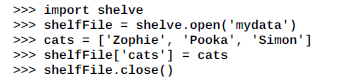

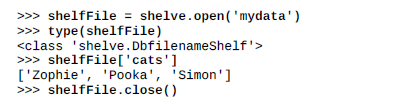

Saving Variables with the shelve Module

The shelve module will let you add Save and Open features to your program.

###os.getcwd()###

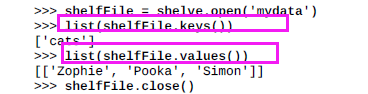

Your programs can use the shelve module to later reopen and retrieve the data from these shelf files. Shelf values don’t have to be opened in read or write mode — they can do both once opened.

Just like dictionaries, shelf values have keys() and values() methods that will return listlike values of the keys and values in the shelf.

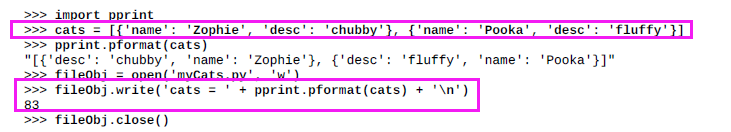

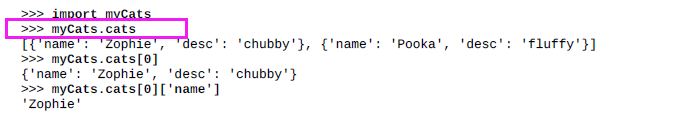

Saving Variables with the pprint.pformat() Function

pprint.pprint() function will “pretty print” the contents of a list or dictionary to the screen

pprint.pformat() function will return this same text as a string instead of printing it

And since Python scripts are themselves just text files with the *.py file extension, your Python programs can even generate other Python programs.

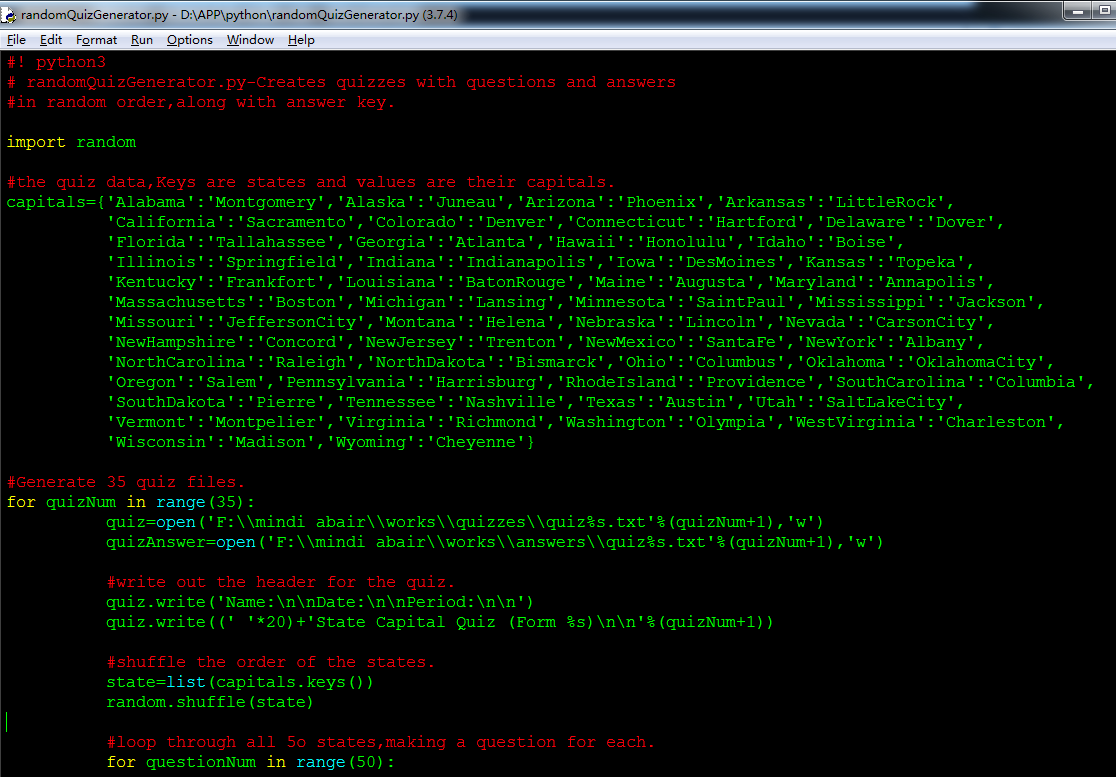

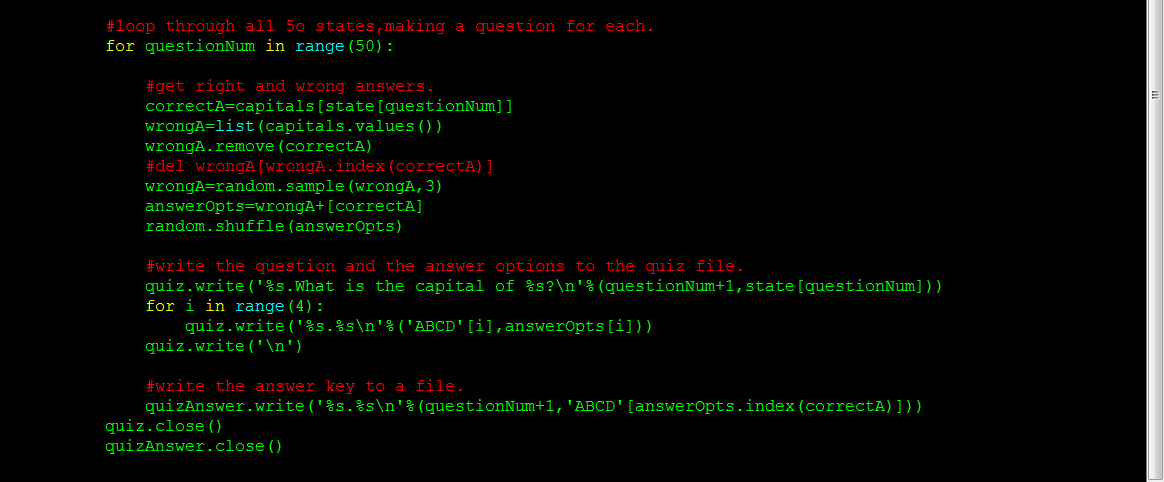

*Project: Generating Random Quiz Files

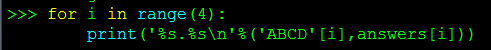

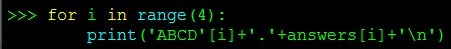

Each time through the loop, the %s placeholder in ‘capitalsquiz%s.txt’ and

‘capitalsquiz_answers%s.txt’ will be replaced by (quizNum + 1)

random.sample() function

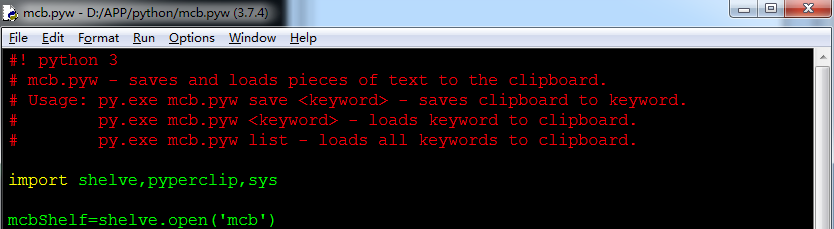

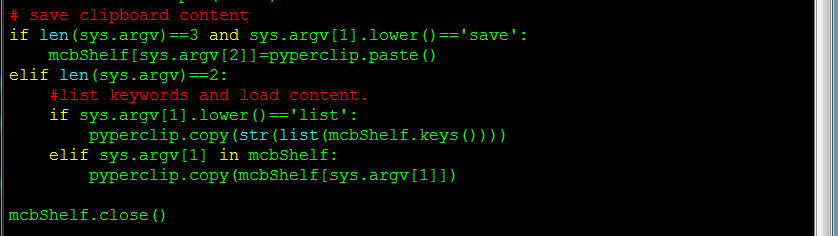

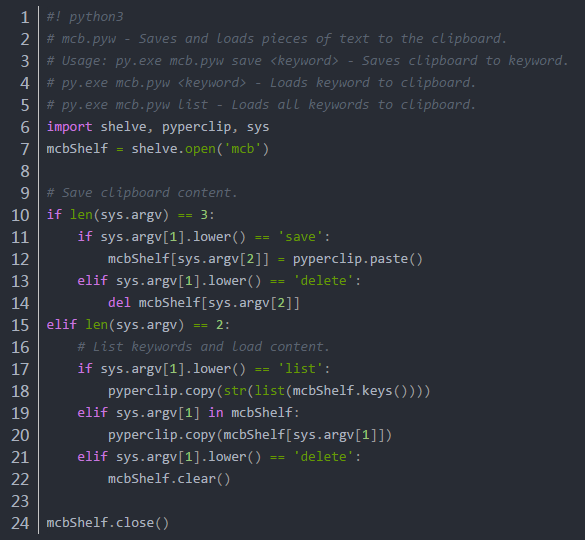

Project: Multiclipboard

The *.pyw* extension means that Python won’t show a Terminal window when it runs this program. (See Appendix B for more details.)